The basic unit of matter could become the basic unit of computing. A

lone atom of phosphorus embedded in a sheet of silicon has been made to

act as a transistor.

It is not the first single-atom transistor, but it can be much more

precisely positioned than its predecessors, potentially making it a lot

more useful.

“It’s an absolutely fantastic piece of engineering,” says physicist

Bruce Kane at the University of Maryland, who was not involved in the

work.

Elaborate production methods would initially prevent single-atom

phosphorus transistors from being a worthwhile addition to traditional

computers, but they may be necessary one day. The devices could also

find an application in futuristic, super-speedy quantum computers.

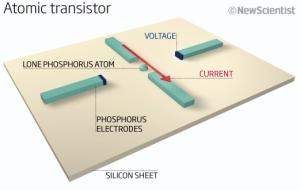

A transistor is essentially a lump of conducting material sitting

between two electrodes that acts as a switch. A pulse of voltage is

supplied by a further electrode,”opening” the switch and allowing

current to flow through the transistor.

Wiggling atom

Combining transistors on a chip produces logic circuits that can

carry out computations. A goal shared by computer chip makers is to

keep shrinking the transistor: squeeze ever more onto a single chip and

you increase its computational power.

To dictate the exact position of their single atom, Michelle Simmons

at the University of New South Wales, Australia, and colleagues started

by covering a silicon sheet with a layer of hydrogen. Then they used

the tip of a scanning tunnelling microscope to remove hydrogen atoms

according to a precise pattern. They exposed two perpendicular pairs of

exposed silicon strips plus a tiny rectangle made of just six silicon

atoms that sat at the junction between these strips (see diagram,

right).

Adding phosphine gas (PH3) and heating caused phosphorus

atoms, which are conducting, to bind to these exposed areas of silicon.

In the case of the rectangle only one atom inserted itself into the

silicon network.

The result was four phosphorus electrodes and a single phosphorus atom.

Boutique operation

One pair of electrodes was separated by a 108-nanometre gap.

Creating a voltage between them allowed current to flow between the two

perpendicular electrodes – separated from each other by just 20

nanometres, through the single phosphorus atom, which acted as a

transistor.

Kane points out that the atomic transistor works at temperatures

below 1 kelvin and that fabrication is difficult. “It’s a very slow,

boutique operation to make one of these,” he says.

Simmons agrees, but counters that the traditional computer makers

may be forced to adopt this technology if they want to make ever

smaller chips. “This is one of the only techniques that allows you to

make single atom devices,” she says.

Physicist Jeremy Levy of the University of Pittsburgh in

Pennsylvania reckons the future of single atom transistors lies in

quantum computers. The spin of the electrons in isolated phosphorus

atoms could serve as qubits, the quantum equivalent of the bits in

today’s computers. Controlling the interaction between qubits requires

knowing the exact location of each one. Now that the location of

individual atoms can be controlled, the next challenge is to link two

of these transistors, Levy says.

Journal reference: Nature Nanotechnology, DOI: 10.1038/nnano.2012.21

No comments:

Post a Comment